When Los Angeles-based cinematographer Quyen Tran was selected to shoot the new film Palm Springs she knew she had a short production schedule, which made her pre-production planning even more critical than usual. In the film, it’s Sarah’s sister’s wedding day in the Southern California oasis of Palm Springs. During the reception, Sarah meets Nyles, and the two decide to abandon their fellow guests in favor of some alone time under the stars. As the desert cools, their passions warm — until an arrow suddenly flies into Nyles’ back, and the couple has to run for cover. Nyles tries to warn Sarah away, but she follows him into a weirdly glowing cave. Then, in the blink of an eye, she finds herself back in her hotel-room bed, and back in time to that same morning, apparently doomed to relive this same day ad infinitum.

When Los Angeles-based cinematographer Quyen Tran was selected to shoot the new film Palm Springs she knew she had a short production schedule, which made her pre-production planning even more critical than usual. In the film, it’s Sarah’s sister’s wedding day in the Southern California oasis of Palm Springs. During the reception, Sarah meets Nyles, and the two decide to abandon their fellow guests in favor of some alone time under the stars. As the desert cools, their passions warm — until an arrow suddenly flies into Nyles’ back, and the couple has to run for cover. Nyles tries to warn Sarah away, but she follows him into a weirdly glowing cave. Then, in the blink of an eye, she finds herself back in her hotel-room bed, and back in time to that same morning, apparently doomed to relive this same day ad infinitum.

Premiering at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, the feature Palm Springs secured distribution in what has been reported to be the biggest sale in the festival’s history. The movie stars Cristin Milioti as Sarah, and Andy Samberg — who also served as a producer — as Nyles. Behind the camera, director Max Barbakow’s creative team included Los Angeles-based cinematographer Quyen Tran.

“As crazy and wacky and kooky as Palm Springs is,” Tran says, “there are a lot of deeper themes that are addressed: Why we are here on this Earth? What do you do with your time? What is love? We wanted to make sure that we respected those themes and that it wasn’t just this insane comedy filled with crazy antics. Max and I wanted to take it very seriously and have people think about it.”

Prior to Palm Springs, Tran had shot the first three episodes of the eight-part Netflix series Unbelievable and wrapped production on the documentary short Brave Girl Rising. After that, she recalls, “I was attached to a movie, but it fell apart at the last minute. But the day the studio called to tell us the movie wasn’t going anymore, I got a call from my agent, who said, ‘We have a script for you. It’s an indie, but it’s really special.’ I read the script, and that afternoon I met with Max, and we just hit it off.”

It’s noteworthy that, for a movie whose comedy is steeped in existential crisis, the hand of fate seems to have been visible in bringing Tran aboard. “It was amazing,” she says. “Things happen for a reason.”

It’s noteworthy that, for a movie whose comedy is steeped in existential crisis, the hand of fate seems to have been visible in bringing Tran aboard. “It was amazing,” she says. “Things happen for a reason.”

Palm Springs would reunite the cinematographer with both Panavision and Light Iron, two of her key partners on Brave Girl Rising. Directed by Martha Adams and Richard Robbins, the documentary was made, Tran explains, “for the nonprofit organization Girl Rising, which campaigns for girls’ education and empowerment. We shot in the Somali refugee camp in Dadaab, Kenya.”

The 20-minute film tells the story of Nasro, a 17-year-old Somali girl who grew up in the refugee camp. The camp, Tran says, is “all she knows, and she speaks beautifully about it. Before we started shooting, we sat down and talked to her for a couple of days, because we really wanted to understand her perspective. It was so beautiful and so pure. We tried to capture that in the documentary. We wanted to elevate that perspective and show the beauty within this refugee camp — the way Nasro saw the world.

“Panavision very generously supported the documentary,” the cinematographer continues. “I shot 90 percent of it on the T Series 35mm. I was really impressed with the minimum focus and the falloff and the color rendition of the T Series. The whole point of the documentary was to have the camera see the way that these refugees see the world, and being able to get up close was critical to bringing that visceral perspective.”

For the documentary’s final color, Tran says, “I brought the project to Light Iron. They’re always so friendly, and they had also done my last indie, The Little Hours.”

Brave Girl Rising marked the cinematographer’s first collaboration with Light Iron colorist Ethan Schwartz, who recalls that Tran “wanted a filmic tone that would give a sense of richness, with nice color separation, and to accentuate certain colors, like red. Texture was also really important, and we played around with different film grains to give it a softness and an organic quality. It felt very natural while still being stylized. Q was really able to capture that environment and its feeling. You get a good sense of the atmosphere — the struggles as well as the hope and the inspiration.”

As she was beginning pre-production on Palm Springs, Tran sought to keep her collaboration with Schwartz going. “During prep, when we were picking a post house for our dailies, that’s when I pitched Light Iron,” the cinematographer recalls.

As she was beginning pre-production on Palm Springs, Tran sought to keep her collaboration with Schwartz going. “During prep, when we were picking a post house for our dailies, that’s when I pitched Light Iron,” the cinematographer recalls.

Schwartz shares that because it was decided at the outset that Light Iron would handle both dailies and final color for Palm Springs, “I was able to talk with Q and say, ‘If there are any scenes you have questions about or if you want me to take a look at anything, don’t hesitate to ask.’ So, going into production, she could have that confidence that I was in the background, ready to help in any way I could. As a colorist, I really like being an open source of information for the DP and the director. I’d rather have the questions come to me before we get into the DI room in case there is something that can happen on set. That way we’re always collaborating to make the best possible project.”

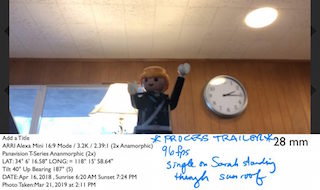

Tran also returned to Panavision for her camera and lens package, which here included Alexa Mini cameras and the T Series optics she had embraced on Brave Girl Rising. “We were asking ourselves, ‘How can we elevate the story even further?’” she remembers. “I suggested anamorphic, and I said, ‘Look, I just shot this documentary with just me and an AC and a DIT. We’ll be fine. Please embrace it. It’ll elevate the movie and give it a special look, because not a lot of comedies are shot in anamorphic.’ Max loved the idea, and we chose the T Series because I wanted to have that minimum focus and I was really comfortable with them, having just shot in a very difficult situation and knowing that we would have to be running and gunning on Palm Springs as well.”

Tran predominantly used focal lengths in the 28mm-40mm range, and she avoided going completely wide open with the aperture. “I like to be at least a third of a stop down just for technical characteristics,” she says. “I hate when things are out of focus, and if I’m doing a super close-up, I’m already giving my focus puller a heart attack — I don’t want to further stress their job. So I’ll go 2.8 1/3 or 2.8-4 split for interiors, and then between a 3 and a 4, or sometimes a 4 ½, for exteriors.”

Tran predominantly used focal lengths in the 28mm-40mm range, and she avoided going completely wide open with the aperture. “I like to be at least a third of a stop down just for technical characteristics,” she says. “I hate when things are out of focus, and if I’m doing a super close-up, I’m already giving my focus puller a heart attack — I don’t want to further stress their job. So I’ll go 2.8 1/3 or 2.8-4 split for interiors, and then between a 3 and a 4, or sometimes a 4 ½, for exteriors.”

Pre-production also saw Tran and Barbakow pull a library of references to help them further define their visual approach.

“Palm Springs is really about love, so we watched comedy-slash-love stories that were unique in tone,” Tran says. “We were really inspired by movies like Punch Drunk Love, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Boogie Nights and The Graduate.

“Having come off of really intense projects like Unbelievable and Brave Girl Rising, I was still in the mindset that there are deeper issues that we need to address, so how do we add to that conversation without taking away from the comedy?” she continues. “For some scenes early on, we did use high-key lighting, and it does seem like a normal rom-com, but that’s a misdirect. We wanted the beginning to be very normal, and then, when things go awry, it allowed for a shift in tone both visually and emotionally.”

The production had just over 20 days for principal photography, which took place entirely on practical locations in the vicinity of Palmdale and Lancaster, California. “We only actually made it to Palm Springs for one day,” Tran recalls. “It took two hours to get there and two hours back, so we only had about six hours to shoot. It was the final scene of the movie, we had to set up a jib — it was crazy. We had every shot storyboarded or shot-listed.”

The production had just over 20 days for principal photography, which took place entirely on practical locations in the vicinity of Palmdale and Lancaster, California. “We only actually made it to Palm Springs for one day,” Tran recalls. “It took two hours to get there and two hours back, so we only had about six hours to shoot. It was the final scene of the movie, we had to set up a jib — it was crazy. We had every shot storyboarded or shot-listed.”

Such time constraints were the rule throughout production. To ensure they could get the most out of their limited hours in each location, Tran and Barbakow were meticulous in their planning during prep. “We even made these Lego diagrams,” the cinematographer reveals. “When we were plotting out the car scenes, Max came over, and I took my kids’ Legos, and we built these sets that I photographed with my Artemis.”

Still, she says, such planning can only take you so far. “In designing shot lists, you have to approach it with the mindset that it may not work,” she offers. “I’ve been an avid gardener for a decade now, and what it’s really taught me is that you sometimes have to cut your losses. When you have a crop that has been infested, you just have to rip it out, because it’s not going to grow and it might contaminate your other crops. Shot lists are a great springboard, but you have to be resilient, and quick on your feet, and not afraid to cut your losses.”

Throughout the shoot, dialogue scenes were conceived to accommodate cross-coverage with two cameras, enabling the actors to improvise and ensuring their spontaneity would be captured. “Allowing the actors to have that space is important,” the cinematographer says. “The only time it was really hard was the campfire scene. It was a night exterior with a huge desert [in the background]. But we got it, and that scene turned out really beautiful emotionally.”

Throughout the shoot, dialogue scenes were conceived to accommodate cross-coverage with two cameras, enabling the actors to improvise and ensuring their spontaneity would be captured. “Allowing the actors to have that space is important,” the cinematographer says. “The only time it was really hard was the campfire scene. It was a night exterior with a huge desert [in the background]. But we got it, and that scene turned out really beautiful emotionally.”

In that scene, Sarah and Nyles are bathed in an orange glow motivated by the fire. Within the world of the movie, Tran says, the color orange “is so important. It represents love. We did not want anything in the movie to be orange except for those very special moments where Nyles and Sarah connect — in the cave and the orange tent, and then with the orange glow from the firelight. Those are the moments when Sarah and Nyles really begin to fall in love with one another.”

Before beginning the final color grade, Tran and Schwartz discussed the visual approach to the project and what the cinematographer was hoping to achieve in the grading suite. “I’ll do my research and look at references, but the conversation is what really gets my creative mind flowing,” Schwartz says. “Just from talking about a certain part of the script, or an experience they had, or what inspired them to shoot a scene a certain way, I’m able to get a sense of the direction we should be going for the look. A large part of my job is to decipher the look and tone from very simple words.”

Schwartz continues, “When I first talked with Q, she mentioned that she was looking at films like The Graduate, Eternal Sunshine and Punch Drunk Love, so going into the DI, I had those movies in the back of my mind. But I also knew this was its own film and it would have its own look. I had a good sense of the mood of the film from her composition and her lighting. All of that really helped to give us a direction.”

Schwartz continues, “When I first talked with Q, she mentioned that she was looking at films like The Graduate, Eternal Sunshine and Punch Drunk Love, so going into the DI, I had those movies in the back of my mind. But I also knew this was its own film and it would have its own look. I had a good sense of the mood of the film from her composition and her lighting. All of that really helped to give us a direction.”

At the time of the grade, Tran recalls, “I was color-timing two other projects, but I really needed to be there for Palm Springs because I wanted to see it through to its completion. [Light Iron’s head of business development and workflow strategy] Katie Fellion and Ethan really worked around my schedule to accommodate that, and I’m forever grateful.”

Once in the grading suite, she says, “Ethan went the extra mile. It wasn’t a simple movie. Even though there are so many repeated scenes, they’re from different angles every time. We had to shoot them from an ‘objective’ camera, from Nyles’ perspective, and from Sarah’s perspective, so it wasn’t like you could just apply a look.”

“The storytelling, the directing and the cinematography all played really well together to give so many different looks, even though we are living in that same day,” Schwartz confirms. He adds, “Q’s a great collaborator to work with in the room. She’s got a strong sense of what she wants, but she also really brings out the creative nature in people.

“Everybody cared so much about this film,” he continues. “Max, Q, Andy, [producers] Akiva Schaffer and Becky Sloviter — every single person who came into the room and who touched this film had such a passion for it. It’s really special.”