Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, the anthology series produced by Sony Pictures Television in a joint venture with Channel 4 in the U.K. and Amazon Studios in the U.S., draws on the late science fiction writer’s voluminous short fiction for its stories of alternate realities, future worlds and paradoxical situations. The show’s first season is a feast for the imagination, consisting of 10 stand-alone, one-hour episodes, each based on a different Philip K. Dick short story and each with a different cast, director and writer. Split between England and the United States, production of Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams was logistically and creatively challenging.

Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams, the anthology series produced by Sony Pictures Television in a joint venture with Channel 4 in the U.K. and Amazon Studios in the U.S., draws on the late science fiction writer’s voluminous short fiction for its stories of alternate realities, future worlds and paradoxical situations. The show’s first season is a feast for the imagination, consisting of 10 stand-alone, one-hour episodes, each based on a different Philip K. Dick short story and each with a different cast, director and writer. Split between England and the United States, production of Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams was logistically and creatively challenging.

“An anthology is different from a normal television series,” says executive producer Michael Dinner. “It’s like doing ten short movies because with each one you’re starting from scratch. There are no standing sets. No standing cast. Each episode is wildly different from the others. Some stories take place in the immediate future, others are set 1,000 years from now.”

One consistent element across the entire series was its sound team. Based at Sony Pictures Studios, Culver City, supervising sound editor Mark Lanza, sound effects editor Harry Snodgrass, dialogue editor Ryne Gierke and their crew worked on all 10 episodes, providing sound elements to support an incredible range of environments, time periods, characters, moods and plots. Their work not only helps to bring the show’s strange worlds to life; they also help tie them together.

“Although the individual episodes are stylistically disparate, they still needed to feel like they came from the same place…the mind of Philip K. Dick,” explains Dinner. “So, I wanted them to have some consistency, mechanically and creatively, in post-production. That ultimately comes from our picture editors, sound editors and mixers.”

On a series with a regular storyline and cast of characters, sound editors build a library of effects that they draw on for recurring situations, props and settings. The library serves as a shorthand that allows the sound editors to keep pace with the typically harried television production schedule. On Electric Dreams, the Sony Pictures sound team enjoyed no such luxury. “None of the effects that we created were ever used a second time,” Lanza observes. “There was no, ‘Oh, we’ve already got that spaceship.’ The only sound that carried over from one show to the next was the title.”

On a series with a regular storyline and cast of characters, sound editors build a library of effects that they draw on for recurring situations, props and settings. The library serves as a shorthand that allows the sound editors to keep pace with the typically harried television production schedule. On Electric Dreams, the Sony Pictures sound team enjoyed no such luxury. “None of the effects that we created were ever used a second time,” Lanza observes. “There was no, ‘Oh, we’ve already got that spaceship.’ The only sound that carried over from one show to the next was the title.”

Individual episodes were treated as distinct sound projects. The first episode to reach the sound team was one titled The Commuter. It tells the story of a melancholic train station attendant who journeys to an idyllic, but imaginary, town. As Lanza recalls, sound plays a big part in telling the story, initially drawing a sharp contrast between the attendant’s real-world environment, which is chaotic and violent, and the pacific fantasy land.

As the story proceeds, the character of the two environments flip. “When the attendant’s outlook begins to change, the two areas change too,” Lanza explains. “His land becomes a little more hospitable and serene and the fantasy world becomes more hostile. We support that transition, very subtly, through sound.”

Finding the right sounds for technology was especially challenging. Due to wide differences in the time settings between the various episodes, sound editors had to imagine how cars, planes and computers might sound at different points in the future. “A spacecraft built ten years from now would sound a lot different from one built in the next millennium,” says Snodgrass. “Each episode had a unique feel based whether it was on Earth or somewhere in space and how far it was set in the future. Some of the hardest parts were simple things, like beeps and glitches. Those little touches couldn’t be the same from show to show.”

Finding the right sounds for technology was especially challenging. Due to wide differences in the time settings between the various episodes, sound editors had to imagine how cars, planes and computers might sound at different points in the future. “A spacecraft built ten years from now would sound a lot different from one built in the next millennium,” says Snodgrass. “Each episode had a unique feel based whether it was on Earth or somewhere in space and how far it was set in the future. Some of the hardest parts were simple things, like beeps and glitches. Those little touches couldn’t be the same from show to show.”

“Seven episodes had a lot of computer technology,” he adds. “We created seven separate libraries of computer sounds to make each episode internally consistent, yet unique and distinct from the rest.”

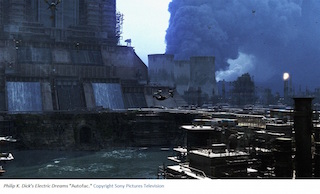

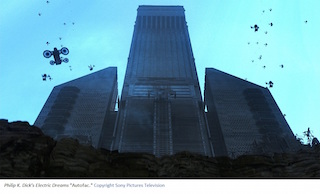

Mixing for the series was split between two stages at Sony Pictures Studios with Elmo Ponsdomenech and Todd Beckett, and Ryan Collins and Nick Offord, as the two mix teams. Collins and Offord drew the assignment of mixing an episode entitled Autofac, set in a post-apocalyptic world.

“Our director, Peter Horton, said there were no more birds or crickets in this world,” recalls Lanza. “So, we did our best in editing to get rid of all that we could. That left Nick and Ryan with several challenges. They needed to cover up what we couldn’t get rid of and compensate for the times we may have pushed the dialogue too far. In a few cases, they went back to the original dialogue and tried to get unwanted elements out of the tracks themselves. There was a delicate balance of machinery to organics in the mix as that was one of the main themes of the episode. I think they nailed it.”

Dinner, who spent five years developing the series, says that employing 10 separate production teams was risky. “I was trying to thread the needle between a traditional series and an anthology series presenting individual points of view on the work of Philip K. Dick,” he says. “In the end, I think that all the directors and writers, both here and abroad, would say that it was a great experience and that we kept their visions intact. It was a wonderful collaboration and the show is one we all feel very good about.”

Sony Pictures Entertainment http://www.sonypictures.com/corp/divisions.html