As part of the Tribeca Film Festival, the Dolby Institute recently brought together sound mixer Skip Lievsay and music supervisor Susan Jacobs, two award-winning filmmakers, to explore scenes from their work and to share their strategies in using sound as a storytelling tool. Glenn Kiser, an accomplished sound designer in his own right, served as moderator.

As part of the Tribeca Film Festival, the Dolby Institute recently brought together sound mixer Skip Lievsay and music supervisor Susan Jacobs, two award-winning filmmakers, to explore scenes from their work and to share their strategies in using sound as a storytelling tool. Glenn Kiser, an accomplished sound designer in his own right, served as moderator.

Lievsay has worked as sound engineer on films by Terrence Malick, Jonathan Demme, John Sayles, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Alfonso Cuaron and has done the sound on all of the Coen Brothers’ films. He recently received the Academy Award for Best Sound for Gravity.

Jacobs has been the music supervisor on a long list of Academy Award-winning films including American Hustle, Silver Linings Playbook, Inside Job and Little Miss Sunshine. Among her many other films are Kansas City, Basquiat, Girlfight and Capote.

Kiser spent eleven years as vice president and general manager of George Lucas’ Skywalker Sound where he oversaw sound design and mixing work on projects including Avatar, Pirates of the Caribbean, Fahrenheit 9/11 and Star Wars. He currently serves as the director of the Dolby Institute and recently directed the comedic short Sabbatical, which is on the festival circuit.

The setting was the Theater 2 Beatrice in the School of Visual Arts in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. The theatre was filled with a mix of younger and older people. When Kiser asked for a show of hands of the filmmakers in the audience most people raised their hands. The panelists seemed to take that as a cue to use the session to teach lessons about the subtle but powerful contributions sound and music can make to any film. They also made it clear that no two films are made in quite the same way – different directors can have widely different methods of working – and one key to success is to try to bring harmony to the production team. Making movies is stressful and it’s important for people to get along.

Lievsay and Jacobs each screened favorite scenes from two of their movies. Both chose one current and one older film. Lievsay’s choices were both Coen Brothers films: Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) and The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001). Jacobs chose director Karen Kusama’s 2000 indie film Girlfight (2000) and David O. Russell’s American Hustle (2013).

First up was a scene from Inside Llewyn Davis. Setting things up for the audience, Lievsay called it his favorite scene in the film and said that he sees it as the pivotal moment in the film. He made it clear that this is not necessarily a view shared by the Coen Brothers. He called it the cat/car scene.

First up was a scene from Inside Llewyn Davis. Setting things up for the audience, Lievsay called it his favorite scene in the film and said that he sees it as the pivotal moment in the film. He made it clear that this is not necessarily a view shared by the Coen Brothers. He called it the cat/car scene.

In the scene, Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaacs) is hitchhiking his way from New York to Chicago to meet with Bud Grossman (F.Murray Abraham), the man who would soon discover and groom Bob Dylan, Davis rides with two musicians: the beat poet Johnny Five (Garrett Hedlund) and jazz musician Roland Turner (John Goodman). At a roadside restaurant, Turner collapses from a heroin overdose. Eventually they get Turner back in the car and later stop on the side of the highway to rest. When a police officer tells them to move on, Johnny Five resists and is arrested, taking the car keys with him. Sitting in the silence of the car Davis ponders what to do. The only sounds are cars streaming past him on the road and a somber guitar solo. Finally Davis climbs out of the car leaving the cat and the unconscious Turner inside. Before he closes the car door he studies the cat for seconds before finally closing the door.

For Lievsay, the cat represents his old life in New York to Davis and he leaves it because he believes Chicago will be a fresh start for him and will lead to success. He’s moving forward. “When he’s looking at the cat, that’s what he’s thinking,” Lievsay said.

He said that the guitar music in that scene was the only piece of scoring in the movie and that it was recorded for another film that Lievsay worked on years ago. He had to fight with the Coen Brothers to include it in the film. Their argument, he said, was that this is a film about music and any music other than what we see played in the film would be extraneous. Lievsay said they had a point adding that, in Llewyn Davis all the music was performed live during the shoot. “What you saw on screen,” said Lievsay “was what we recorded.” His point was that the scene needed music at that moment to emphasize all the emotions that Davis was feeling sitting in the car. The Coen Brothers accepted his argument and the music stayed.

Girlfight is an American sports drama film and was the debut of screenwriter and director Karyn Kusama. It was also the film debut of Michelle Rodriguez and was a breakout role for her. The movie follows Diana Guzman (Rodriguez), a troubled teen who decides to channel her aggression by training to become a boxer, despite the skepticism of both her abusive father and the prospective trainers in the male-dominated sport. In the scene Jacobs chose we see Guzman sparring in a boxing gym and the sounds are those of punches being thrown, trainers shouting instructions and onlookers offering a mix of support and ridicule. As the scene plays out we also hear fast-paced piano music racing as if trying to beat the fighters to the finish.

Girlfight is an American sports drama film and was the debut of screenwriter and director Karyn Kusama. It was also the film debut of Michelle Rodriguez and was a breakout role for her. The movie follows Diana Guzman (Rodriguez), a troubled teen who decides to channel her aggression by training to become a boxer, despite the skepticism of both her abusive father and the prospective trainers in the male-dominated sport. In the scene Jacobs chose we see Guzman sparring in a boxing gym and the sounds are those of punches being thrown, trainers shouting instructions and onlookers offering a mix of support and ridicule. As the scene plays out we also hear fast-paced piano music racing as if trying to beat the fighters to the finish.

Jacobs said she asked a young musician, Theodore Shapiro, to compose some music for the film and the song in that scene was what he came up with. It became the title theme. Jacobs said the Charles Mingus song, Ysabel’s Table Dance, inspired her. She also made the point that it’s almost always less expensive to commission new music than to acquire the rights for existing music. She cautioned about the potential danger of working with a composer and asking him or her to do music like they’ve done before. She said they’re inevitable response will be, “Stop ripping me off.”

Jacobs noted that fifteen years ago was a very different era as far as music is concerned and the Girlfight soundtrack ended up having more monetary value than the film. “In those days, you could still make deals with the record companies,” she said. “They were open to working with us.”

Even in that era, though, she made the point that obtaining the rights for popular songs was and remains almost always out of reach of all but the biggest budget films. “Source music is very, very expensive,” she said. “As a rule of thumb if you or your mother recognize a song, you can’t afford it.”

Almost as an aside, Jacobs recalled a conversation about music that she had with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman when the two were working on director Bennett Miller’s Capote (2005).

In the film New Yorker writer Truman Capote (Hoffman) travels to Kansas with his friend writer Harper Lee (Catherine Keener) to research a story about the murder of four of the members of the Clutter family. Capote intends to interview those involved with the victims, the Clutter family, with Lee as his go-between and facilitator. The scene Jacobs mentioned involves a teenage girl meeting with Capote and Lee in a soda shop. A corner jukebox played music.

Jacobs said that Hoffman seemed a bit skeptical that the choice of music on the jukebox could have much of a dramatic an impact on the scene. She showed him the scene first with a song that evoked the emotions that the teenage girl in the scene was likely feeling. The song was full of emotion and drew the viewer into the scene, making the girl very sympathetic. The second choice was a more generic ‘50s rock song and had the effect of letting the viewer pull back from the action on the screen. She said her point (which Hoffman accepted) was that “Music really changes the way a scene plays. Music either pulls you in the scene or distances you from it.”

Jacobs said one of the most important questions any filmmaker can ask about anything in a film is, “How do you want to feel?” She said the sound supervisor’s main job is to find a composer and/or music for the director and the goal is “facilitating a director’s vision.”

That led to her second choice of films. The scene she selected was one of the many memorable scenes from David O. Russell’s American Hustle. In it Irving Rosenfeld (Christian Bale) and his wife Rosalyn (Jennifer Lawrence) are having dinner in an Italian restaurant Mayor Carmine Polito (Jeremy Renner) and his wife Dolly (Elizabeth Rohm). This is the scene that Lawrence all but dominates when she insists everyone smell her favorite nail polish. The scene ends when she laughs so hard she literally falls off her chair.

That led to her second choice of films. The scene she selected was one of the many memorable scenes from David O. Russell’s American Hustle. In it Irving Rosenfeld (Christian Bale) and his wife Rosalyn (Jennifer Lawrence) are having dinner in an Italian restaurant Mayor Carmine Polito (Jeremy Renner) and his wife Dolly (Elizabeth Rohm). This is the scene that Lawrence all but dominates when she insists everyone smell her favorite nail polish. The scene ends when she laughs so hard she literally falls off her chair.

Jacobs said that for that scene in particular and for most of the movie Russell wanted music that evoked the Italian-American experience. She said she and the director both understood a big challenge was, “How do you make it not seem like a Scorsese movie?”

Individual viewers will judge how well they succeeded on that score but, working with a limited budget, Jacobs answered the challenge by using music from obscure Italian movies from the past. She said the music from the restaurant scene came from an erotic Italian film of the ‘40s.

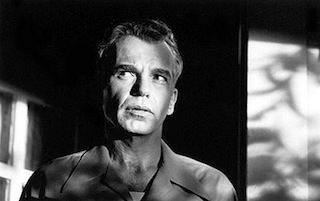

The final screening was Lievsay’s choice, the Coen Brothers The Man Who Wasn’t There.

The Man Who Wasn’t There, which is set in 1949, was shot in black and white. In the film Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a barber in Santa Rosa, California, is married to Doris (Frances McDormand), a bookkeeper with a drinking problem. Doris is having an affair with her boss at Nirdlinger's, the local department store, “Big Dave” Brewster (James Gandolfini), a loud, boisterous man, who constantly brags about his combat adventures in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. This being a Coen Brothers movie, complications including murder ensue and Ed finds himself convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Ed writes his story on death row as he awaits execution. A men’s pulp magazine is paying him by the word. While waiting on death row, he dreams of walking out to the prison courtyard and seeing a flying saucer, to which he reacts with a simple nod. To tell more would spoil the end for anyone who hasn’t seen the movie.

The Man Who Wasn’t There, which is set in 1949, was shot in black and white. In the film Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a barber in Santa Rosa, California, is married to Doris (Frances McDormand), a bookkeeper with a drinking problem. Doris is having an affair with her boss at Nirdlinger's, the local department store, “Big Dave” Brewster (James Gandolfini), a loud, boisterous man, who constantly brags about his combat adventures in the Pacific Theatre during World War II. This being a Coen Brothers movie, complications including murder ensue and Ed finds himself convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair. Ed writes his story on death row as he awaits execution. A men’s pulp magazine is paying him by the word. While waiting on death row, he dreams of walking out to the prison courtyard and seeing a flying saucer, to which he reacts with a simple nod. To tell more would spoil the end for anyone who hasn’t seen the movie.

The scene Lievsay selected included the end of the trial and Ed’s final days on death row. While the scene contains somber music and appropriately stark sound effects, what prompted Lievsay to show it, he said, was “the balance of music and sound effects but particularly Thornton’s voiceover. It turns the idea of cinema upside down.” This is very much a first-person film. Thornton’s rich, baritone voice dominates the movie to the point that it becomes, in a very positive way, radio. Yet this is radio with lush black and white images shot by cinematographer Roger Deakins. Susan Jacobs described the scene this way: “It’s so intimate.”

During a brief question and answer session Jacobs said the movie music business is in a state of flux because at the moment union musicians are now fighting to be paid for movies made in the ‘70s. “Everybody’s trying to figure it out,” she said. Regardless of the politics of the business she said, the creative issues remain the same and she urged young filmmakers to always “challenge and experiment.” She concluded with this advice: “Before money is even discussed, ask everyone, ‘Do you want to be involved with this project?’”