Movie audiences today are being led to believe that streaming has made the entire history of cinema available for a simple subscription fee — or at least a couple of dozen subscription fees. This is not true. There is an immediate and critical need to address this issue. The truth is that movies are simply not as available today as they were during the heyday of VHS when some brick-and-mortar video stores carried tens of thousands of titles. Now, with a few giant companies controlling the most popular streaming services and trying to outdo one another with original content, many older movies are being left behind.

Movie audiences today are being led to believe that streaming has made the entire history of cinema available for a simple subscription fee — or at least a couple of dozen subscription fees. This is not true. There is an immediate and critical need to address this issue. The truth is that movies are simply not as available today as they were during the heyday of VHS when some brick-and-mortar video stores carried tens of thousands of titles. Now, with a few giant companies controlling the most popular streaming services and trying to outdo one another with original content, many older movies are being left behind.

Thousands of movies are either completely lost or are deemed too small to warrant the expense of restoring them, and thus are completely unavailable. This is especially true of work created by women and people of color. As a result, we end up with a skewed history of filmmaking and crucial gaps in our cultural knowledge and legacy.

Filmmakers Mary Harron, Shola Lynch, Nancy Savoca, Ira Deutchman and Richard Guay; entertainment lawyer Susan Bodine; and archivist/distributors Dennis Doros and Amy Heller have joined forces to create a new organization, Missing Movies, to address the problem of lost films — movies that are no longer available because of confusion about rights and ownership, difficulties in locating original materials, and the lack of a business model to support the creation of restorations suitable for the current marketplace.

Filmmakers Mary Harron, Shola Lynch, Nancy Savoca, Ira Deutchman and Richard Guay; entertainment lawyer Susan Bodine; and archivist/distributors Dennis Doros and Amy Heller have joined forces to create a new organization, Missing Movies, to address the problem of lost films — movies that are no longer available because of confusion about rights and ownership, difficulties in locating original materials, and the lack of a business model to support the creation of restorations suitable for the current marketplace.

The idea for Missing Movies began when Savoca and Guay discovered that their 1993 film Household Saints could not screen in a retrospective at Columbia University because of problems with all three of the issues above. According to Savoca, “we began an extensive research project, and with the help of our lawyer, Sue Bodine and the original distributor of the film, Ira Deutchman, we were finally able to create a scenario where the film could be made available again. In talking to other filmmakers about our journey, we realized that many other films — particularly independent films made in the 1980s and 1990s — were in similar straits.”

Last November, Savoca and Guay organized a panel discussion with the Directors Guild of America to share their concerns with other filmmakers. It was this panel that brought together the group that has created Missing Movies and written the Manifesto that is part of today’s announcement.

Last November, Savoca and Guay organized a panel discussion with the Directors Guild of America to share their concerns with other filmmakers. It was this panel that brought together the group that has created Missing Movies and written the Manifesto that is part of today’s announcement.

Many filmmakers are unprepared — financially or logistically — to embark on the research and financial commitment to recover their own lost films. The group has discovered that many award-winning movies — including some that premiered at prestigious film festivals — are completely unavailable for audiences to see on any platform or format.

Some examples are Victor Nuñez’s Gal Young ‘Un; Marcel Ophuls’ Memory of Justice; Mirra Bank, Ellen Hovde, and Muffie Meyer’s Enormous Changes at the Last Minute; Glen Pitre’s Belizaire the Cajun; Sherman Alexie’s The Business of Fancy Dancing; and Bill Couturié’s Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam.

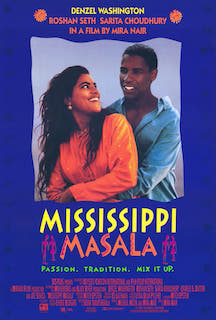

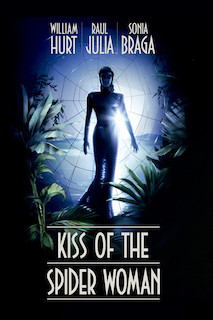

Others include Baby Face Nelson (1957, Don Siegel), Black Girl (1972, directed by Ossie Davis), Eat the Document (1972, directed by D.A. Pennebaker and Bob Dylan), The Heartbreak Kid (1972, directed by Elaine May), Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985, directed by Hector Babenco), and Mississippi Masala (1991, directed by Mira Nair)

Others include Baby Face Nelson (1957, Don Siegel), Black Girl (1972, directed by Ossie Davis), Eat the Document (1972, directed by D.A. Pennebaker and Bob Dylan), The Heartbreak Kid (1972, directed by Elaine May), Kiss of the Spider Woman (1985, directed by Hector Babenco), and Mississippi Masala (1991, directed by Mira Nair)

The group’s mission statement reads in part:

“Missing Movies’ long-term goal is to preserve a critical and beloved art form — one that is vitally important to the history of our time. To that end, we plan to advocate for revisions in copyright law and for changes in some industry standards for working with filmmakers.

“We seek to formally create a non-profit organization that can facilitate and fund these efforts. To start, Missing Movies will focus on American independent films — including features, documentaries, shorts, and experimental films — but we hope to broaden our scope as work progresses.

“Missing Movies looks forward to working with like-minded organizations, including specialty streamers, archives, festivals, distributors, film labs, trade unions, foundations, and a wide range of filmmakers, to find effective solutions to this critical, often-ignored problem.

Click here for a list of films that have already been identified as in need of saving and to read the full Missing Movies Manifesto http://missingmovies.org

For more information, contact Nancy Savoca at [email protected] or Richard Guay at [email protected].