By Doug Darrow

Few words are as overused by the cinema industry as the word immersive. We at Dolby are perhaps guiltier than most. We’ve used the term in dozens of press releases and marketing materials, most recently when describing Dolby Atmos. Immersive seemed like a good word to describe a cinema sound experience so lifelike that moviegoers felt as if they were immersed in the very environment where the film took place. It suited the radical new approach of Dolby Atmos to audio: one that placed and moved sound objects to create a virtual reality of sound in the auditorium itself.

Few words are as overused by the cinema industry as the word immersive. We at Dolby are perhaps guiltier than most. We’ve used the term in dozens of press releases and marketing materials, most recently when describing Dolby Atmos. Immersive seemed like a good word to describe a cinema sound experience so lifelike that moviegoers felt as if they were immersed in the very environment where the film took place. It suited the radical new approach of Dolby Atmos to audio: one that placed and moved sound objects to create a virtual reality of sound in the auditorium itself.

Unfortunately, many in the industry used the term to describe any new cinema audio format—even new formats based on traditional, channel-based approaches. This created confusion, as references to immersive audio formats lumped together two dramatically different approaches to sound—an 11.1 channel-based approach similar to Dolby Digital 5.1 and Dolby Surround 7.1, and Dolby Atmos, the first and only object-based sound platform for cinema. This confusion created concern among some exhibitors that the industry might be approaching an immersive audio format war.

But there is no cinema audio category called immersive. Barco Auro’s traditional 11.1 channel-based approach is closer to Dolby Surround 7.1 than to Dolby Atmos. Exhibitors now have an option to either invest in a legacy channel-based format—be it 5.1, 7.1, or 11.1—or in the future of cinema audio with the only available object-based audio format, Dolby Atmos.

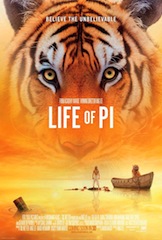

The introduction of the first object-based approach to creating, rendering, and playing back cinema sound marked a giant step forward in the evolution of cinema sound, an evolution that took us from mono to stereo to multichannel surround and now, to object-based audio in the form of Dolby Atmos. The creative community loves using Dolby Atmos because object-based audio lets them be much more inventive when using sound to draw an audience into a story. This isn’t just about adding height, but about adding the precision of movement that made one journalist write that he felt he had to duck to avoid space debris while watching Star Trek into Darkness. It is the same realism that made countless moviegoers inadvertently hold their breaths during the storm scene in Life of Pi.

With Dolby Atmos, filmmakers don’t have to think in terms of speakers or channels (though they can still integrate multichannel sound as needed). Instead, they give each sound object specific directions as to where it should be placed or move. For example, the sounds associated with a bird would have metadata indicating the bird’s movements within the auditorium. The sound as it chirps, flaps its wings, and lands on an overhead branch with rustling leaves can then be represented in the theatre as clearly as if you were hearing it during a hike through a thick forest.

With Dolby Atmos, filmmakers don’t have to think in terms of speakers or channels (though they can still integrate multichannel sound as needed). Instead, they give each sound object specific directions as to where it should be placed or move. For example, the sounds associated with a bird would have metadata indicating the bird’s movements within the auditorium. The sound as it chirps, flaps its wings, and lands on an overhead branch with rustling leaves can then be represented in the theatre as clearly as if you were hearing it during a hike through a thick forest.

Best of all, the system is intelligent enough to create the illusion intended—despite variations in the size, shape, and speaker configuration of each theatre—to ensure the artist’s intent remains intact, from the studio in which it was mixed to the cinema.

While filmmakers and sound designers appreciate how Dolby Atmos engages moviegoers’ senses, executives at studios and postproduction houses are excited because its object-based approach radically simplifies work flows. A native Dolby Atmos mix can be used to create 5.1-, 7.1-, or even 11.1-channel versions.

Exhibitors have expressed enthusiasm for object-based audio as well. In recent months, both the National Association of Theatre Owners and Union internationale des cinémas, which represent exhibitors in North America and Europe, respectively, have expressed a desire for clear standards for object-based audio.

Dolby welcomes the industry’s interest in standards. Dolby has been a leading contributor to cinema standards for more than 40 years, from the original B-chain work in use worldwide to the standards enabling digital cinema and now object-based sound. More than a year ago, Dolby backed a study group within the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers to find common approaches among several different sound systems and explore methods for common implementations, including object-based audio. As part of this effort to define packaging and synchronization for object-based audio, Dolby drove SMPTE ad-hoc subgroups along with such industry leaders as Avid, Christie, GDC, and several major studios. In recent weeks, DTS has also gotten involved in object-based standards, submitting a SMPTE proposal for object-based sound based on the Multi-Dimensional Audio format they have been promoting since early 2012. However, the MDA format, which received great attention when it was first announced in early 2012 by SRS Labs (since acquired by DTS), has so far gained no significant traction among filmmakers, sound designers, cinema exhibitors, or others in the industry.

Dolby welcomes the industry’s interest in standards. Dolby has been a leading contributor to cinema standards for more than 40 years, from the original B-chain work in use worldwide to the standards enabling digital cinema and now object-based sound. More than a year ago, Dolby backed a study group within the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers to find common approaches among several different sound systems and explore methods for common implementations, including object-based audio. As part of this effort to define packaging and synchronization for object-based audio, Dolby drove SMPTE ad-hoc subgroups along with such industry leaders as Avid, Christie, GDC, and several major studios. In recent weeks, DTS has also gotten involved in object-based standards, submitting a SMPTE proposal for object-based sound based on the Multi-Dimensional Audio format they have been promoting since early 2012. However, the MDA format, which received great attention when it was first announced in early 2012 by SRS Labs (since acquired by DTS), has so far gained no significant traction among filmmakers, sound designers, cinema exhibitors, or others in the industry.

As the only company that has successfully deployed object-based audio in hundreds of cinemas, we at Dolby want to ensure that any relevant standards work has the benefit of our real-world experiences. Other members of the relevant SMPTE subgroups agree. To date, we have more than 75 Dolby Atmos titles released or committed to worldwide, more than 300 screens installed or committed to globally, endorsements from award-winning directors, and a state-of-the-art sound experience that has been described as an “auditory virtual reality.”

Anything the industry can do to formally endorse the move to object-based audio is beneficial to the cinema industry as a whole. The recently announced Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) addendum validates the importance of object-based audio and sends a clear signal to exhibitors that DCI supports and believes in the future of what Dolby has created—with the industry and for the industry. In fact, the existing Dolby Atmos end-to-end system was designed in a way that it still meets the requirements of the new DCI addendum. DCI’s support for object-based audio will help focus the discussion and promote participation in the existing SMPTE groups working on standards for object-based audio.

However, establishing new standards takes time, which is why we continue to open up our Dolby Atmos platform to third-party manufacturers. Dolby has open specifications that are free for any third party to use. GDC recently incorporated Dolby Atmos playback into its servers, and Christie just announced that its Integrated Media Block now supports Dolby Atmos. We know that many in the cinema industry also plan to follow.

In the end, our standards efforts are guided by two main goals: one, end-to-end quality control to ensure that the filmmaker’s vision is delivered and played back intact at the cinema, so that audiences have the exact experience intended by the creative team; and two, technically correct and useful standards that will stand the test of time.

Doug Darrow is senior vice president, cinema, Dolby Laboratories