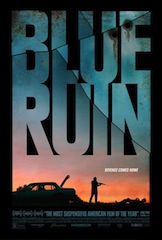

I recently attended the seventh annual Art House Convergence, a four-day gathering of more than 400 people from all over the world who are devoted to making, distributing and showing quality films. The event, held under the auspices of Sundance, is devoted to the idea that cinema should be promoted and cherished as one of the world’s most important art forms. What’s interesting, though, is that where some people see real value in a particular film, others see vapid entertainment. Which may explain why filmmaker Jeremy Saulnier felt the need to apologize for the fact that his movie, Blue Ruin, which was screened there is a genre film. And that’s the art house paradox.

I recently attended the seventh annual Art House Convergence, a four-day gathering of more than 400 people from all over the world who are devoted to making, distributing and showing quality films. The event, held under the auspices of Sundance, is devoted to the idea that cinema should be promoted and cherished as one of the world’s most important art forms. What’s interesting, though, is that where some people see real value in a particular film, others see vapid entertainment. Which may explain why filmmaker Jeremy Saulnier felt the need to apologize for the fact that his movie, Blue Ruin, which was screened there is a genre film. And that’s the art house paradox.

The four-day event was held at the Zermatt Resort in the quiet mountain town of Midway, Utah.

Russ Collins, executive director and CEO of the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor, Michigan and chairman of the Art House Convergence welcomed first time attendees and told them the main role of all art house cinemas is to “work intelligently to engage your community in a love of film.”

The opening keynote speaker was Ira Deutchman who asked, “How do we harness the spirit of cooperation, and the potential power of a group that keeps growing year after year?”

Deutchman, a producer, distributor and marketer of independent films is a co-founder and managing partner of Emerging Pictures, a New York-based digital exhibitor. He is also chair of the film program at Columbia University School of Arts. He said, “What we have in this room are a group of committed people who are self-identifying as ‘mission driven,’ while actually having many different missions. You also self-identify as Art Houses, which is also somewhat ill defined since one person’s art is another’s trash. I’m not suggesting that this is a bad thing, but it requires some understanding in order to take this group and maximize its potential. Clearly, there is not a singular mission in the room.”

There are many examples of large and successful organizations that are made up of essentially like-minded people who have very different viewpoints and agendas; the Democratic and Republican parties are two that come immediately to mind. Closer to home and to this discussion, once upon a time the National Association of Broadcasters convention was actually basically about the needs and concerns of American TV stations. Today, however, more than one hundred thousand people from all over the globe gather in Las Vegas for a week every April to discuss virtually every kind of production, post-production and distribution media technology.

Thus, finding people with an exactly identical world-view is not a requirement when it comes to building a successful and useful venue where people can discuss a wide range of shared needs. And it takes very little time to conclude that the people of the art house cinema world tend to be mavericks – in the most positive sense of that word – because it seems obvious that only mavericks can succeed in any aspect of the independent cinema world.

Thus, finding people with an exactly identical world-view is not a requirement when it comes to building a successful and useful venue where people can discuss a wide range of shared needs. And it takes very little time to conclude that the people of the art house cinema world tend to be mavericks – in the most positive sense of that word – because it seems obvious that only mavericks can succeed in any aspect of the independent cinema world.

Understanding all these issues the Art House Convergence has wisely chosen not to stifle anyone’s independence and instead is broadening its scope even further. To that end this year’s event, which attracted more than 100 new attendees, made a concerted effort to include film festivals and filmmakers. Among the filmmakers in attendance were Genevieve Bailey and her partner Henrik Nordstrom, who probably would have won the award for having traveling the farthest to the event. They came from Australia and were there mainly to network and to promote their award-winning documentary I Am Eleven.

The idea of bridging the gap between filmmakers and exhibitors has always made sense to me. There will probably always be a need for movie distributors but that does not mean that filmmakers and exhibitors should not make a stronger effort to connect with one another, if only to better understand the needs and issues they have in common.

Two surveys conducted by the Bryn Mawr Film Institute and presented during the conference painted a cautiously positive outlook for the future of art house cinemas. Much of the information the surveys contain is not surprising. For example, as with their more mainstream counterparts most successful art house cinemas are in more upscale urban and suburban areas, have multiple screens, converted to digital cinema early and show a lot of first run Hollywood and independent movies. They also show a growing portfolio of alternative content including opera, theatre, concerts and community-oriented program. And they have liquor licenses, which adds significantly to their profits.

Juliet Goodfriend, who created the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, a non-profit film education and exhibition center in a once-threatened historic theater in suburban Philadelphia, presented the findings of the surveys. I found the audience reaction to one statistic very telling, especially given how difficult it is becoming to obtain film prints of any kind and the fact that film projectors are the key contributor to the damage caused to movie prints. Goodfriend said that, according to her survey, more than two-thirds of all art house cinemas say they plan to hold onto at least one 35mm projector, even if they have or plan to convert to digital. The audience responded to that bit of news with loud, enthusiastic applause and hoots and cheers of joy. It was as if some important truths could only be found in 35mm film.

Juliet Goodfriend, who created the Bryn Mawr Film Institute, a non-profit film education and exhibition center in a once-threatened historic theater in suburban Philadelphia, presented the findings of the surveys. I found the audience reaction to one statistic very telling, especially given how difficult it is becoming to obtain film prints of any kind and the fact that film projectors are the key contributor to the damage caused to movie prints. Goodfriend said that, according to her survey, more than two-thirds of all art house cinemas say they plan to hold onto at least one 35mm projector, even if they have or plan to convert to digital. The audience responded to that bit of news with loud, enthusiastic applause and hoots and cheers of joy. It was as if some important truths could only be found in 35mm film.

An overwhelming and not so positive conclusion to be drawn from both surveys is that the art house cinema audience consists mainly of people 55 and older. The surveys also point out the obvious fact that young people in growing numbers seem to prefer watching movies on small screens. The question for movie theatres of all kinds – but art houses in particular – is how to attract younger viewers back to the big screen.

One way is to get younger people more directly involved in the exhibition process, whether it’s a film festival or an art house cinema and the conference gave clear examples of how that’s not just possible but is being done. In particular, one panel discussion I attended had as its goal exploring “how we as a field can improve what should be a mutually beneficial relationship with the people creating what we show.” Its panelists included moderator Andy Smith, Nickelodeon Theatre; Dominick Balletta, Jacob Burns Film Center; Holly Herrick, Austin Film Society; and the aforementioned Jeremy Saulnier, director of the film Blue Ruin.

Saulnier gave a personal example of how important viewing the first rough cut of his movie on a big screen was. He shot the film on small digital cameras and did most of the editing on a computer in his Brooklyn apartment. A tireless networker he was able to got the attention of the Brooklyn collaborative effort UnionDocs and they allowed him to show his film-in-progress on their big screen. Saulnier said the feedback he got from that evening was devastating but ultimately incredibly valuable. Based on the comments of the audience that night he completely changed his film, which is being distributed by Radius. Saulnier strongly suggested that his movie might not have been picked up had he not seen it on the big screen with a live audience. Speaking for all filmmakers, he said, “We need that community, that physical space.”

Dominick Balletta agreed and said the Jacob Burns Film Center, which is in Pleasantville, New York, regularly holds rough-cut screenings and invites people to attend for free. They never tell the audience in advance what they will be seeing, he said, but nevertheless the events have become very popular with moviegoers and valuable for filmmakers. Balletta gave an example of an Egyptian filmmaker, now living in New York, who was surprised and discouraged that the Jacob Burns audience apparently got none of the jokes and slang references in his movie. But he learned from the experience and was able to improve his film.

Holly Herrick of the Austin Film Festival said her organization has for a long time had an application process that filmmakers can use to get their works in progress screened.

Several exhibitors in the audience said they have had great success bringing filmmakers in to talk about their movies during screenings and suggested the experience was valuable for audiences and filmmakers alike. Increasingly these Q&A sessions are done via Skype and one exhibitor said Skype sessions were usually more relaxed because the filmmakers felt more comfortable in their own surroundings.

In the conclusion to his opening keynote address Ira Deutchman challenged the group with a call to action, namely to use its growing influence to become a positive force in the industry.

In the conclusion to his opening keynote address Ira Deutchman challenged the group with a call to action, namely to use its growing influence to become a positive force in the industry.

“What do I mean by that?” he asked. “When the studios and the major chains have their next sit-down over technological standards, and start making deals that change the fundamental economics of the business, this group deserves a place at the table. I feel the same way about being force-fed the results of the DCI initiative. We deserve a place at that table.”

He encouraged the group to work with other organizations in the expensive but desperately needed effort to preserve America’s threatened film archives and to work collectively to demand that the government contribute funding to that cause. In all these endeavors he challenged the Art House Convergence to use its growing size and influence to advance their shared goals. “If we are not making the case,” he asked, “who will?”

Click here to read Ira Deutchman’s entire keynote address http://iradeutchman.com/

Click here to download the NATIONAL AUDIENCE SURVEY today!

Click here to download the ART HOUSE THEATER OPERATIONS SURVEY today!